Large shifts towards automation, robots, and artificial intelligence have been uprooting the labor market. Computing power has grown exponentially, thus leading to great advances in artificial intelligence, with applications that span diverse tasks, from self-driving cars to cancer detection. While these advances improve the working lives and leisure activities of some, they also pose a threat to the jobs of many workers. With the Covid-19 pandemic accelerating the development and adoption of new technologies to replace human labor, it is important to understand how the threat posed by pending automation will impact today's society. In this paper, we analyze survey data from a representative sample of almost 4,300 workers in the United States (US) to document individual perceptions of the current automation threat and workers' responses to this perceived risk. We further embed an information experiment in our survey to introduce exogenous variation in workers' beliefs about the automation threat. The information experiment allows us to study how perceptions about automation risk causally affect workers' political attitudes, preferences for redistribution, and job responses.

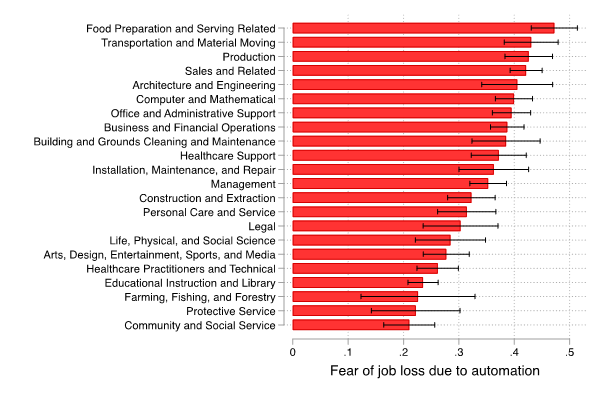

Two main sets of findings emerge from the project we have done with the generous help of the Keynes Fund. First, workers are on average concerned about the threat of automation to their jobs within the next 10 years. More specifically, we ask ``On a scale of 0-100%, how likely do you think it is that you might lose your job/not find a job due to automation, robots and artificial intelligence within the next 10 years?''. Respondents to our survey fear displacement through technology with an average probability of 35%, and almost 40% of respondents believe they have a probability of being replaced by a machine, robot or algorithm that is higher than 50%. The average perceived automation risk is higher for less educated and younger respondents. Strikingly, we find age to play a very important role amongst high earning workers. Amongst workers younger than 40 in the top earnings decile, the perceived probability of displacement is nearly 50%, while for older workers in the top earnings decile this probability is less than 30%. We also document large differences across occupations. As can be seen in Figure 1, workers in education community or social services and protective services on average fear to lose their jobs due to automation with a probability of less than one quarter. In contrast, the same probability is nearly one half for workers working in food preparation and serving related jobs, or in transportation and material moving.

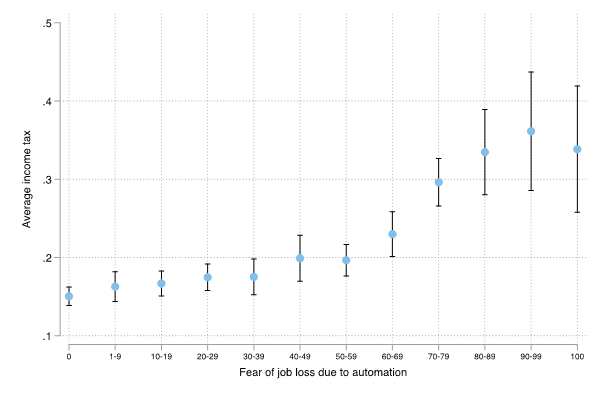

Second, we look at how workers preferences, attitudes, and intentions relate to this perceived automation threat in a descriptive and causal manner. In response to a perceived threat of job loss because of automation, workers can, roughly speaking, respond along multiple margins. They can turn to the state and request more redistribution or welfare. They can differentiate themselves vertically by upskilling, or horizontally by changing occupations. Or they can save to self-insure against the potential future shock. In this paper we study the first two margins, i.e. changes in political preferences and employment responses. We provide correlational evidence that perceived automation risk strongly relates to preferences for redistribution, employment responses, populist attitudes and voting intentions. Focusing on participants assigned to the control group, we find that fear of losing one's job due to automation is positively related to intentions to retrain or switch occupations, as well as higher taxation and more redistribution. Many of these relationships are pronounced. As can be seen in Figure 2, workers without fear of being displaced by robots within the next ten years favor an average income tax rate below 15%. In contrast, those fearing displacement with certainty request one-third of income to be tax ed on average.

However, these correlations might be driven by other observed or unobserved factors and cannot be interpreted causally. Therefore, we provide evidence of a causal effect of fear of automation on workers' preferences, attitudes and behaviors using the results of our information experiment. To overcome endogeneity concerns related to the perceived automation threat, we design an information treatment that introduces exogenous variation in workers' beliefs about the automation risk. More precisely, we randomize participants into a control group that receives no information, and two treatment groups where participants are provided with information about the potential automation risk faced by workers in their occupation, and we compare this number to respondents' own perceived risk. Given that before treatment assignment we ask workers about their perceived automation risk, our treatment creates good news and bad news, as some workers are exposed to a job loss probability that is lower than the probability they perceived, and others to one that is higher.

The information about automation risk that we provide to treated respondents relies on a previous data collection carried out in 2020 as part of the Covid Inequality Project (covidinequalityproject.com for the surveys). In the study, members of the United States labor force were asked how likely they thought it was that they might lose their job within the next ten years due to automation. With responses to this question at hand, we compute average automation risks for different occupations. We then present treated participants to our survey with the number that corresponds to the automation threat in their own narrow occupation category. The aim of the paper is not to defend these measures of automation risk, which is extremely difficult to predict due to uncertainty and endogeneity surrounding future innovations. Rather, our goal is to use this constructed measure of average perceived automation threat to introduce variation in workers' beliefs.

Our information experiment features one control group and two treatment groups. While all treated respondents receive information on the automation probability that comes from the Covid Inequality Project data, the two treatments differ in the stated source of the information. More precisely, some respondents are told that the information they see comes from a study by expert economists from the University of Oxford (the ‘experts’ treatment) and others are told that the information refers to the opinion of people working in similar jobs as theirs (the ‘people’ treatment. This allows us to study whether workers respond differently to information coming from experts, i.e., a socially distant group, or people that are similar to them.

Our experiment shows that information provision leads to significant treatment effects on preferences for redistribution. Treated respondents' preferred tax rate on income and their preferred level of universal basic income payments increases with the difference between the probability of job loss they are exposed too and their own prior. For support for government funded adult retraining programs we find a symmetric response; workers exposed to good news reduce their support while those expose to bad news increase it. However, we do not document a significant causal effect of the automation threat on employment responses as measured by propensity to participate in a retraining program and switch occupation. Instead, workers exposed to bad news intend to protect their job by joining a union. This evidence is suggestive of the fact that the future automation trends will lead to more support for redistribution and a larger welfare state, but not to increased differentiation through upskilling or re-skilling.

Moreover, workers exposed to bad news are more likely to consider their ideology to be left rather than right wing, while those exposed to good news report higher trust in politicians. These polarizing attitudes go hand in hand with a common problem of modern democracy, whereby good news increases the likelihood of wanting to vote in the next presidential elections, while bad news decreases it. Turning to whether workers react differently to information coming from different sources, we find mild differences in treatment effect depending on whether the information was phrased as coming from experts or other workers similar to the respondent, with the people treatment leading to a greater impact on preferences for redistribution.

Our findings instead suggest that the impact of the automation threat on ‘winners’, those receiving good news, is rather muted, while those exposed to bad news adapt their attitudes significantly. Indeed, most of the treatment effects that we document are driven by workers exposed to a higher job loss probability than they perceived. Looking at magnitudes, some of the before-mentioned effects are considerable. Being exposed to a 50 to 100 percentage point higher job loss probability than perceived increases the preferred mean tax rate by 0.4 percentage points and increases the desired level of UBI by 76 log points.

The project has been presented at an invited inaugural lecture of the Phd program at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona and a research seminar at Trinity College Dublin. In December the findings will be presented at the conference of the Spanish Economic Association in Valencia.

This project has already generated 3 Faculty of Economics and Janeway Institute working papers and 2 published papers, in the Journal of Public Economics and Fiscal Studies Special Issue: The COVID‐19 Economic Crisis.

Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys

Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys, Abi Adams-Prassl, Teodora Boneva, Marta Golin and Christopher Rauh, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 189 (2020)

We present real time survey evidence from the UK, US and Germany showing that the immediate labor market impacts of Covid-19 differ considerably across countries. Employees in Germany, which has a well-established short-time work scheme, are substantially less likely to be affected by the crisis. Within countries, the impacts are highly unequal and exacerbate existing inequalities. Workers in alternative work arrangements and who can only do a small share of tasks from home are more likely to have lost their jobs and suffered falls in earnings. Women and less educated workers are more affected by the crisis.

Furloughing

Furloughing, Abi Adams-Prassl, Teodora Boneva, Marta Golin and Christopher Rauh, Fiscal Studies Special Issue: The COVID‐19 Economic Crisis, Vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 591-622 (2020)

Over nine million jobs were furloughed in the United Kingdom during the coronavirus pandemic. Using real-time survey evidence from the UK in April and May 2020, we document which workers were most likely to be furloughed and we analyse variation in the terms on which they furloughed. We find that women were significantly more likely to be furloughed. Inequality in care responsibilities seems to have played a key role: mothers were 10 percentage points more likely than fathers to initiate the decision to be furloughed (as opposed to it being fully or mostly the employer's decision) but we find no such gender gap amongst childless workers. The prohibition of working whilst furloughed was routinely ignored, especially by men who can do a large percentage of their work tasks from home. Women were less likely to have their salary topped up beyond the 80 per cent subsidy paid for by the government. Considering the future, furloughed workers without employer-provided sick pay have a lower willingness to pay to return to work, as do those in sales and food preparation occupations. Compared with non-furloughed employees, furloughed workers are more pessimistic about keeping their job in the short to medium run and are more likely to be actively searching for a new job, even when controlling for detailed job characteristics. These results have important implications for the design of short-time work schemes and the strategy for effectively reopening the economy.

The Impact of Fear of Automation

The Impact of Fear of Automation, Marta Golin and Christopher Rauh, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics (2022)

In this paper, we establish a causal effect of workers’ perceived probability of losing one’s job due to automation on preferences for redistribution and intentions to join a union. In a representative sample of the US workforce, we elicit the perceived fear of losing one’s job to robots or artificial intelligence. We document a strong relationship between fear of automation and intentions to join a union, retrain and switch occupations, preferences for higher taxation, higher government handouts, populist attitudes, and voting intentions. We then show a causal effect of providing information about job loss probabilities on preferred levels of taxation and handouts. In contrast, our information treatment does not affect workers’ intentions to self-insure by retraining or switching occupations, but it increases workers’ self-reported likelihood of joining a union to seek more job protection. The treatment effects are mostly driven by workers who are informed about larger job loss probabilities than they perceived.